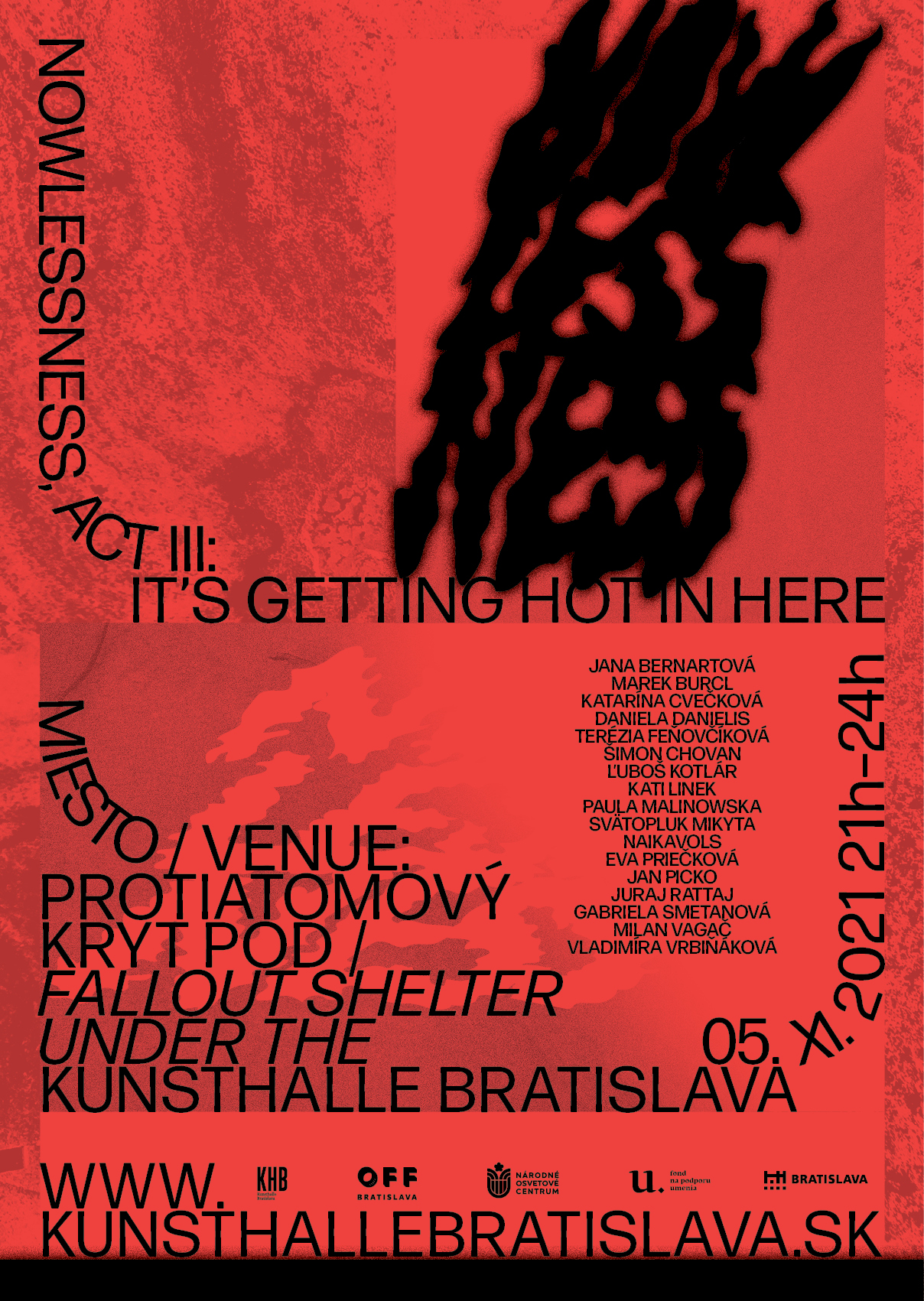

5 November 2021

fallout shelter under Kunsthalle Bratislava

Bratislava, Slovakia

exhibiting and participating artists:

Jana Bernartová, Marek Burcl, Katarína K. Cvečková, Daniela Danielis, Terézia Feňovčíková, Šimon Chovan, Ľuboš Kotlár, Kati Linek, Paula Malinowska, Svätopluk Mikyta, NaiKavols, Eva Priečková, Jan Picko, Juraj Rattaj, Gabriela Smetanová, Milan Vagač, Vladimíra Vrbiňáková

curators: Ľuboš Kotlár, Erik Vilím

production: Erik Vilím

visual identity: Dávid Koronczi

technical support: Ján Gašparovič

translation: John Minehane

photo documentation: Leontína Berková

video documentation: Denis Kozerawski

partners: Kunsthalle Bratislava, NOC, Festival OFF Bratislava

fallout shelter under Kunsthalle Bratislava

Bratislava, Slovakia

exhibiting and participating artists:

Jana Bernartová, Marek Burcl, Katarína K. Cvečková, Daniela Danielis, Terézia Feňovčíková, Šimon Chovan, Ľuboš Kotlár, Kati Linek, Paula Malinowska, Svätopluk Mikyta, NaiKavols, Eva Priečková, Jan Picko, Juraj Rattaj, Gabriela Smetanová, Milan Vagač, Vladimíra Vrbiňáková

curators: Ľuboš Kotlár, Erik Vilím

production: Erik Vilím

visual identity: Dávid Koronczi

technical support: Ján Gašparovič

translation: John Minehane

photo documentation: Leontína Berková

video documentation: Denis Kozerawski

partners: Kunsthalle Bratislava, NOC, Festival OFF Bratislava

nature

and the gallery space

The attempt at a thinking which does not respect primary binary oppositions, such as, for example, natural/artificial, technological/organic, human/extrahuman, outer/inner, us/them or male/female, is nothing new; we find it already in the 1980s,when it was generated against the background of techno-humanist ideas and the struggle to be first in the conquest of outer space. But before we can be aware of what this really means, it is necessary to go back in time and understand the broader circumstances which today are leading us towards a new view of things. One of the examples in which one can plainly see the separateness of culture and nature is the concept, created by modernist thinking, of the white cube. Specifically, in the idea of a gallery space that is radically demarcated from external reality, via the absence of windows and the overall neutrality of its interior, which is stripped of traces of past, present or future. The flat walls seem to suggest that what is found between them does not have any direct relation to nature, apart from imitating it visually. The white cube creates an appearance of being a sacred place devoted to silent aesthetic contemplation. It is a place deprived of the signs of social reality and surrounding nature, which is characterised by timelessness.

undermining and domination of the subject

Modernism, under the influence of 19th century aesthetic ideas, had its own reasons for defending the autonomy of cultural activities. It was following on from the classical division of nature and culture in the western tradition. Today, however, we find ourselves in an entirely different world, and the environmental consequences of the industrial revolution, which “drove the motor” of progress in the first half of the 20th century, and of our cherished idea of the dominance and infallibility of human rationality, are visible and palpable all around us. Deprived of the vision of the gods, as modernist people we took to ourselves the conviction that nature is something passive, separated from us and dependent on the thinking subject, which is found at the centre of everything and has power to shape all things and transform them. Human, and hence also cultural, activity has had (and continues to have) a devastating impact, which is without precedent in the planet’s history. Through its own expansion, in forming conditions on the planet the human species has thus come next in line from the other natural elements that changed environmental conditions (meteorite, volcanoes, tectonic plates). This thinking – centred on humans as the privileged beings of this planet – have brought us to a breaking point, where our original idea of absolute control over nature is falling apart, together with our capacity to anticipate possible scenarios for the future. All of this reveals to us the answer to the question: why is anthropocentrism “undermined”, right to its foundations, among philosophers at the present time?

plants speak

Dualist thinking is peculiar to human beings. It is a kind of universal principle describing the being of things, the world, and ourselves within it. However, if we want to show a recognition of reality where the strict and firm binary oppositions (for example, human and non-human) are lost, we can go deeper into the past. In his text Beyond Nature and CulturePhilippe Descola analyses animist, naturalist and totemic tendencies in archaic society, while attempting to illustrate how the categories of nature/culture or subjective/objective are wiped away. We may take animism as an example: in this belief plants, animals and other entities are endowed with subjectivity. They may thus share individual relationships between themselves and the human being; equally, they may have social characteristics and ethical rules; they may become part of rituals or mythological stories. That is to say, they are conceived of as part of a passive exteriority. Human and extra-human beings take a similar cultural view of their own daily lives, inasmuch as they share a similar kind of subjectivist status, but they have a different surrounding world (or object) – they discover it differently and use it differently, depending on their particular individual physical equipment. Animism, according to Descola, creates elementary categories enabling a social practice in which the dualities of natural/cultural or human/extra-human lose significance.

The attempt at a thinking which does not respect primary binary oppositions, such as, for example, natural/artificial, technological/organic, human/extrahuman, outer/inner, us/them or male/female, is nothing new; we find it already in the 1980s,when it was generated against the background of techno-humanist ideas and the struggle to be first in the conquest of outer space. But before we can be aware of what this really means, it is necessary to go back in time and understand the broader circumstances which today are leading us towards a new view of things. One of the examples in which one can plainly see the separateness of culture and nature is the concept, created by modernist thinking, of the white cube. Specifically, in the idea of a gallery space that is radically demarcated from external reality, via the absence of windows and the overall neutrality of its interior, which is stripped of traces of past, present or future. The flat walls seem to suggest that what is found between them does not have any direct relation to nature, apart from imitating it visually. The white cube creates an appearance of being a sacred place devoted to silent aesthetic contemplation. It is a place deprived of the signs of social reality and surrounding nature, which is characterised by timelessness.

undermining and domination of the subject

Modernism, under the influence of 19th century aesthetic ideas, had its own reasons for defending the autonomy of cultural activities. It was following on from the classical division of nature and culture in the western tradition. Today, however, we find ourselves in an entirely different world, and the environmental consequences of the industrial revolution, which “drove the motor” of progress in the first half of the 20th century, and of our cherished idea of the dominance and infallibility of human rationality, are visible and palpable all around us. Deprived of the vision of the gods, as modernist people we took to ourselves the conviction that nature is something passive, separated from us and dependent on the thinking subject, which is found at the centre of everything and has power to shape all things and transform them. Human, and hence also cultural, activity has had (and continues to have) a devastating impact, which is without precedent in the planet’s history. Through its own expansion, in forming conditions on the planet the human species has thus come next in line from the other natural elements that changed environmental conditions (meteorite, volcanoes, tectonic plates). This thinking – centred on humans as the privileged beings of this planet – have brought us to a breaking point, where our original idea of absolute control over nature is falling apart, together with our capacity to anticipate possible scenarios for the future. All of this reveals to us the answer to the question: why is anthropocentrism “undermined”, right to its foundations, among philosophers at the present time?

plants speak

Dualist thinking is peculiar to human beings. It is a kind of universal principle describing the being of things, the world, and ourselves within it. However, if we want to show a recognition of reality where the strict and firm binary oppositions (for example, human and non-human) are lost, we can go deeper into the past. In his text Beyond Nature and CulturePhilippe Descola analyses animist, naturalist and totemic tendencies in archaic society, while attempting to illustrate how the categories of nature/culture or subjective/objective are wiped away. We may take animism as an example: in this belief plants, animals and other entities are endowed with subjectivity. They may thus share individual relationships between themselves and the human being; equally, they may have social characteristics and ethical rules; they may become part of rituals or mythological stories. That is to say, they are conceived of as part of a passive exteriority. Human and extra-human beings take a similar cultural view of their own daily lives, inasmuch as they share a similar kind of subjectivist status, but they have a different surrounding world (or object) – they discover it differently and use it differently, depending on their particular individual physical equipment. Animism, according to Descola, creates elementary categories enabling a social practice in which the dualities of natural/cultural or human/extra-human lose significance.

It is interesting to add that, compared to modern western

human-centred

thinking, the comparable animist tendencies have a longer history.

bad trip

We may, however, offer an example from a past closer to ourselves (the 1960s/70s), where the application of basic binary oppositions is lost and logic ceases to be dominant. I have in mind a state under the influence of psychotropic drugs (“a bad trip”), when our brain is assaulted by an external substance that evokes specific cerebral resonances. Essentially, it is a reaction to a chemical substance where rationality is suppressed and the structure of the world may be newly ordered. Such a state is often described as a kind of fusion with the universe in one whole, as an awareness of mutual cosmological coexistence. It is defined by a disablement of the dominating ego – the “I”, as it were, is diffused in the multiplicity of things. What is interesting, though, is the relationship that is created here. “I” is assaulted by an external agent (the drug), which takes over control of the visual interpretation of the surrounding world (a vision or loss of perception of time and space).The subject thus ceases to be the privileged arbiter of perception.

technology and nature

The theme of non-binarity, or loss of oppositions in thinking, is very broad. One of the further places where it can be illustrated is technology itself, which is recent decades has been experiencing a rapid acceleration of development. As an object of examination through the optics of the new materialism, it is seen and interpreted primarily in relation to the planet. We may take as an example our mobile apparatuses, which offer a broad spectrum of cultural and social activities, 24 hours daily. More precisely, we are referring to smartphones with Li-ion batteries, which are manufactured from cobalt. As we know, the second largest supplier on earth is the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and the extraction of this mineral has invidious environmental and social effects in that country. From this perspective, technology appears as something that is not autonomous, dematerialised, or separated from nature. The new materialism thus has the ambition to analyse technologies not reduced to what we as human beings think of them; digital apparatuses are personalised and become active agents which influence not just the course of nature but also, in a radical way, our everyday lives. Jussi Parikka, media theoretician, frames this conjunction of cultural conquests and nature with the concept of “natureculture”, following on, of course, from Donna Haraway, the concept’s author. For this reason among others, Parikka remains one of the most inspiring theoretical authorities of the present time.All of these examples may inspire us in seeking other possible ways of thinking about and understanding nature and our place in it. The new materialism, queer theory, or the aforementioned animism: those are all simply different perspectives for looking at the (co)existence of human and extra-human beings. Needless to say, they are not perfect; they have their snares, and it is necessary to think them through critically in more depth and be watchful when applying them in practice.

artistic artefacts speak

All of our movements of thought have foundations in experience, emotions, or the senses, and therefore art claims a privileged place in philosophical imagination. For this reason, the eventact iii: it’s getting hot in here has a kind of “strange” atmosphere, which provokes our sensual perception. Here we may lose ourselves (physically and in thought), but also find ourselves anew. Similarly to the above-mentioned examples of thinking, likewise the objects and works in the space of a nuclear bomb shelter may become stimuli of our imagination, causing it at least partly to break through the limits of the binary conception of the world. They are not something neutral; quite the contrary, they complement one another in significance, and indeed give enrichment independently of the artist’s control. They are occupying this specific space for a short time, and here they develop the work of removing strict conceptual oppositions with far greater understanding than this text.

Erik Vilím

bad trip

We may, however, offer an example from a past closer to ourselves (the 1960s/70s), where the application of basic binary oppositions is lost and logic ceases to be dominant. I have in mind a state under the influence of psychotropic drugs (“a bad trip”), when our brain is assaulted by an external substance that evokes specific cerebral resonances. Essentially, it is a reaction to a chemical substance where rationality is suppressed and the structure of the world may be newly ordered. Such a state is often described as a kind of fusion with the universe in one whole, as an awareness of mutual cosmological coexistence. It is defined by a disablement of the dominating ego – the “I”, as it were, is diffused in the multiplicity of things. What is interesting, though, is the relationship that is created here. “I” is assaulted by an external agent (the drug), which takes over control of the visual interpretation of the surrounding world (a vision or loss of perception of time and space).The subject thus ceases to be the privileged arbiter of perception.

technology and nature

The theme of non-binarity, or loss of oppositions in thinking, is very broad. One of the further places where it can be illustrated is technology itself, which is recent decades has been experiencing a rapid acceleration of development. As an object of examination through the optics of the new materialism, it is seen and interpreted primarily in relation to the planet. We may take as an example our mobile apparatuses, which offer a broad spectrum of cultural and social activities, 24 hours daily. More precisely, we are referring to smartphones with Li-ion batteries, which are manufactured from cobalt. As we know, the second largest supplier on earth is the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and the extraction of this mineral has invidious environmental and social effects in that country. From this perspective, technology appears as something that is not autonomous, dematerialised, or separated from nature. The new materialism thus has the ambition to analyse technologies not reduced to what we as human beings think of them; digital apparatuses are personalised and become active agents which influence not just the course of nature but also, in a radical way, our everyday lives. Jussi Parikka, media theoretician, frames this conjunction of cultural conquests and nature with the concept of “natureculture”, following on, of course, from Donna Haraway, the concept’s author. For this reason among others, Parikka remains one of the most inspiring theoretical authorities of the present time.All of these examples may inspire us in seeking other possible ways of thinking about and understanding nature and our place in it. The new materialism, queer theory, or the aforementioned animism: those are all simply different perspectives for looking at the (co)existence of human and extra-human beings. Needless to say, they are not perfect; they have their snares, and it is necessary to think them through critically in more depth and be watchful when applying them in practice.

artistic artefacts speak

All of our movements of thought have foundations in experience, emotions, or the senses, and therefore art claims a privileged place in philosophical imagination. For this reason, the eventact iii: it’s getting hot in here has a kind of “strange” atmosphere, which provokes our sensual perception. Here we may lose ourselves (physically and in thought), but also find ourselves anew. Similarly to the above-mentioned examples of thinking, likewise the objects and works in the space of a nuclear bomb shelter may become stimuli of our imagination, causing it at least partly to break through the limits of the binary conception of the world. They are not something neutral; quite the contrary, they complement one another in significance, and indeed give enrichment independently of the artist’s control. They are occupying this specific space for a short time, and here they develop the work of removing strict conceptual oppositions with far greater understanding than this text.

Erik Vilím

Milan Vagač: BAU_2.0170521; acrylic on canvas

Svätopluk Mikyta: after fight; blown glass, hard drive

Ľuboš Kotlár, Katarína K. Cvečková: untitled (from the series nowlessness); performance

(performer: Eva Priečková)

Juraj Rattaj: Untitled (from the series Zootopia); mixed media, plaster relief, readymade

Jana Bernartová, Jan Šicko, Kati Linek: Sound and Look of NoWood; 3D print

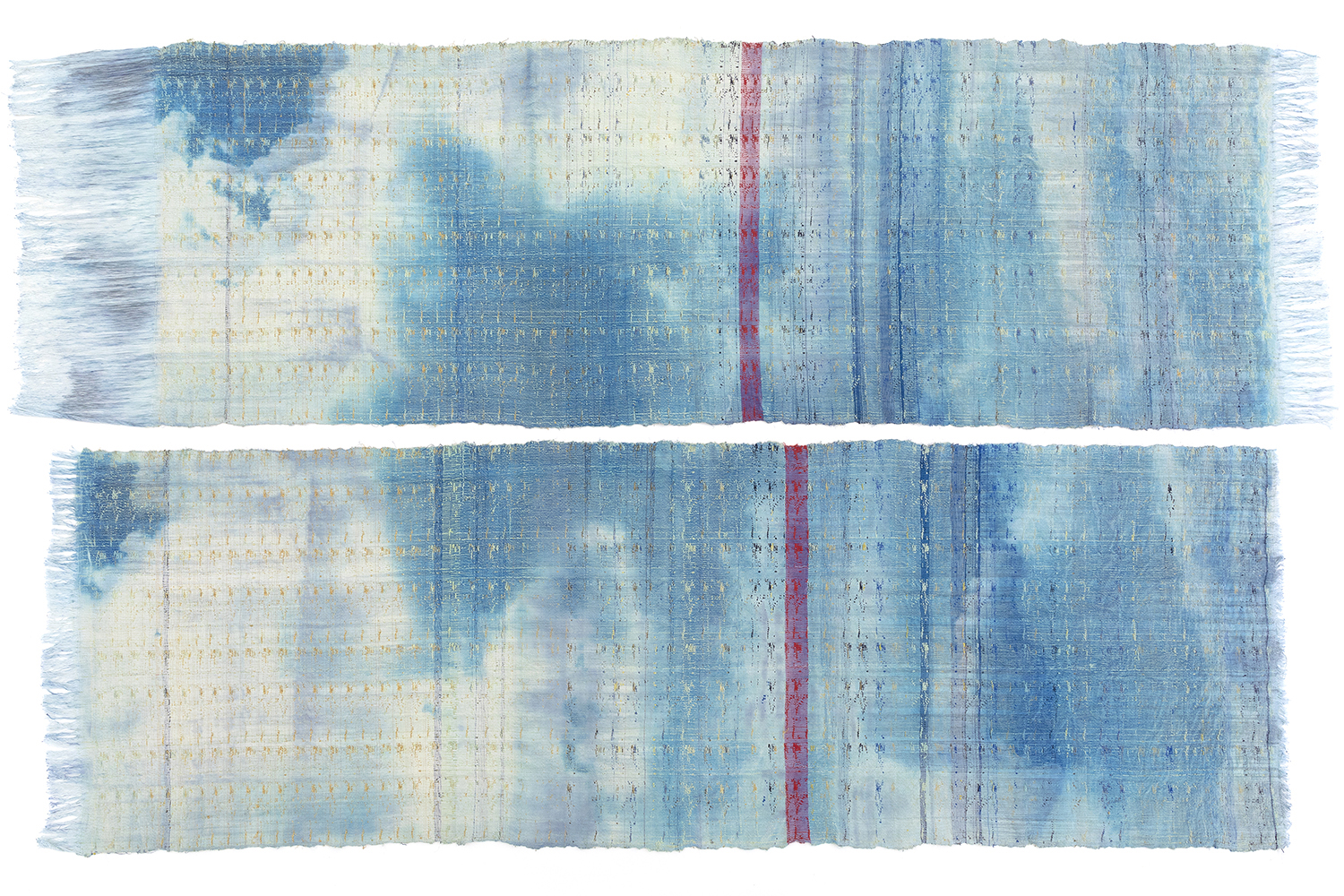

procesual tapestry, wool, leon thread, UV print, textile pigments, cyanotype

Ľuboš Kotlár, Katarína K. Cvečková: untitled (from the series nowlessness);

performance (performer: Gabriela Smetanová)

Šimon Chovan: untitled (sketch from the Organs of Routine); screen, silicon, pump, micro driver

Marek Burcl: untitled; copper galvanic sculpture of plant

Ľuboš Kotlár: untitled (from the series nowlessness); daguerreotype

Ľuboš Kotlár, Paula Malinowska, NaiKavols, Vladimíra Vrbiňáková, Katarína K. Cvečková:

untitled (from the series nowlessness); video

untitled (from the series nowlessness); video